The World’s Flattest Floor

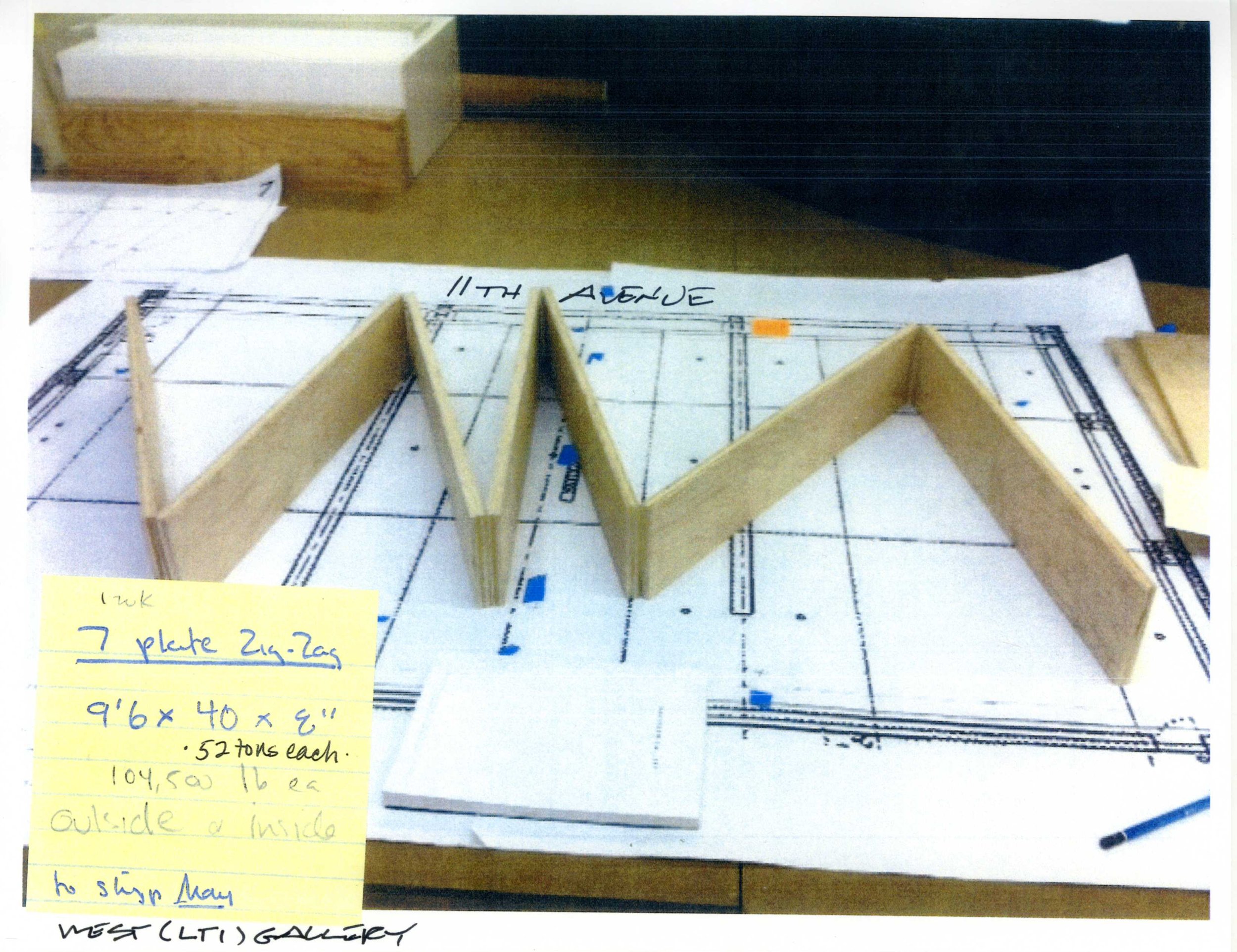

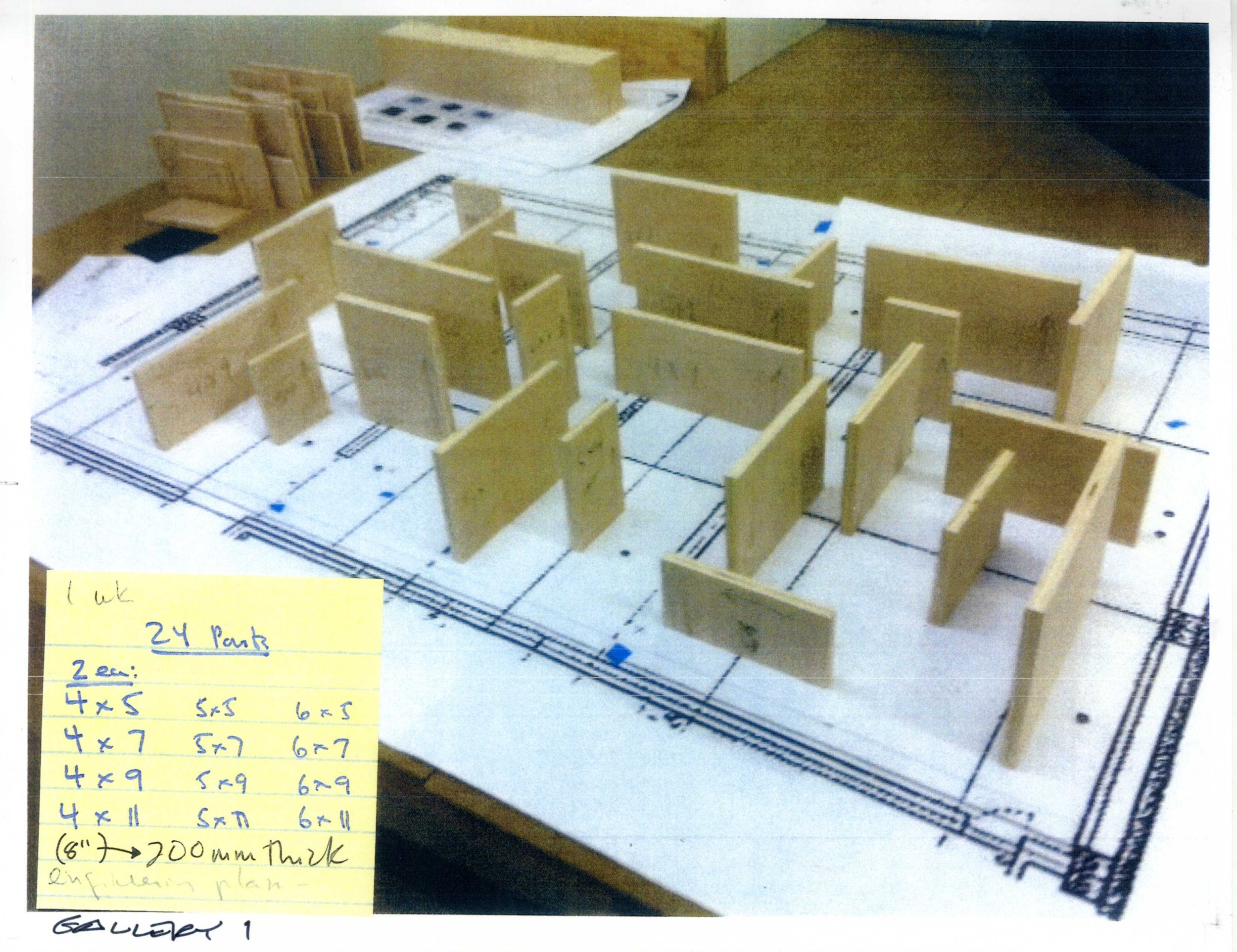

To save the reader the disappointment suffered by the writer, I should start by saying that we ended up just putting shims underneath the sculptures to stabilize them. But, at first, the Artist told us that shims were totally unacceptable, or a string of expletives to that effect, which I heard reverberate across the open-plan office from the Architect’s speakerphone. “Why can’t you make a flat fucking floor?!” the Artist demanded to know, and the Architect’s reasonable attempts to explain that our practice designed the Gallery fifteen years ago, and concrete tends to creep over time, and the Gallery was built on landfill, and the site used to be in the Hudson River, did nothing to tranquilize the situation. The Artist’s studio was preparing for two simultaneous shows of new sculpture at the Gallery’s Chelsea locations to open a couple of months later, so a solution was urgently needed. On W. 21st Street would be a set of curved steel sculptures, the kind for which the Artist is wellknown. But, on W. 24th Street, he had planned a series of tall flat steel plates to stand on their edges, which were only eight inches thick. While the curved pieces naturally support themselves based on their shape, the flat pieces lack such geometric advantages, and would be like playing cards standing on end.

Shadow between steel sculptures and concrete floor, with pen for scale.

As I learned shortly after the phone call concluded, the floor of the Gallery on W. 24th Street was not very flat. Although not visible to the naked eye, its subtly varied surface became apparent when compared to the straight laser-cut edge of steel. This is not atypical for concrete floors; since concrete is poured as a liquid and cures at an uneven rate across its surface, some irregularity is inevitable. But for this show, the Engineer told us we needed the floor to be very flat in order to not risk the sculptures tipping over. The Artist’s concern was less about the plates tipping over than about the uneven shadow lines underneath the sculptures in the irregular gaps between the wavy surface of the floor and the dead straight edge of the steel. But the risk was real. A couple of years earlier, I had watched the riggers and art-handlers install a show of the Artist’s curved pieces at the 24th Street Gallery, so I knew that it was a dangerous process. The massive pieces of steel were shipped from Germany to the port in Elizabeth, New Jersey and then transferred onto low-boy trailers for transport on the roadways, accompanied by police escort across the George Washington Bridge in the middle of the night. The riggers used cranes to bring the pieces off the low-boys and delicately onto a set of air-cushioned dollies, which they then gingerly guided under the loading doors of the Gallery. One piece, as they were removing the dollies from underneath it to set it on the floor, began to wobble back and forth, and all the riggers hastily stepped backwards and let it fall. The interior wall of the Gallery crumpled under the sculpture’s weight as it came crashing onto the concrete floor with a terrible sound. No one got hurt, but the potential was always present.

The Engineer was a gentle and soft-spoken man who taught at a nearby university in his spare time. His office had been one of the lead structural consultants on the World Trade Center towers, and their collapse had been hard on him. In order to stabilize the sculptures on the uneven floor, he suggested placing shims between the floor and the steel wherever the two did not meet. In this way, the sculptures would continuously bear on the ground. But the shims would be visible, and the Artist’s studio could not accept them. Visible shims, they said, would reduce the tension between an abstract geometric relationship—a vertical plane standing on a horizontal plan—and a foreboding material reality—huge plates of industrial steel appearing to balance precariously. “Why can’t you make a flat fucking floor?!” therefore became my marching orders, and I was tasked to figure out how to make the floor of the Gallery flat enough to keep the sculptures stable.

I started with the Internet. The search terms, “world’s flattest floor” returned the information I was looking for more quickly than I expected. A company based in San Diego claimed to have built the flattest concrete floor in the world for a fulfillment warehouse in California. As I learned from their website, the floors of such warehouses must be as flat as possible, because any turbulence…

…continued in Issue 31.

David R. Shanks is an architect and an Assistant Professor at Auburn University’s School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture. He is co-founder of the award-winning architectural practice ASDF, which was named among the best new firms in the United States by The Architect’s Newspaper in 2021. David received his M.Arch from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in 2009, and he has practiced in several globally recognized offices, such as Skidmore Owings and Merrill, Gluckman Tang Architects, Preston Scott Cohen, and Office for Metropolitan Architecture. He has exhibited, presented, and published his work both domestically and internationally, in venues such as the Boston Society of Architects, the Biennale di Architettura di Pisa, and the Journal of Architectural Education. From 2018-2020, he served as Architecture Program Director at Syracuse University’s study abroad campus in Florence, Italy. David has been a resident fellow of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust and the MacDowell Colony.