A Tent for Lovers / A Garden for Pollinators

^1 Duboy, Philippe, Robin Middleton, Francis Scarfe, and Brad Divitt, Lequeu, an Architectural Enigma (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1987), 60.

^2 Lequeu, Jean- Jacques, “Tavern and Hammock of Love,” In Civil Architecture, Morgan Library & Museum. New York City.

“The hammock of love lies in the small garden of the most agreeable delights,” the visionary architect Jean-Jacque Lequeu wrote in 1810.^1 This text described a plate illustrating an intimate space “inside a lush garden that contains flowers producing the ‘odor of paradise.’”^2 A space designed, of course, exclusively for human pleasure.

Hidden in a clearing between the manicured Rose Gardens and wild forests of the Crane Estate in Ipswich, Massachusetts, lies an updated version of Lequeu’s romantic design. A folly that celebrates assemblages within and across species—a heterotopia that blends the boundaries between human and non-human agents.

01 A Tent For Lovers. The project initiates binding processes across species, enabling the shared cohabitation of humans and non-humans. Humans, plants, pollinators, and bacteria constitute a sympoietic system enabled by architecture.

02 Diagram of the folly’s symbiotic mechanism. In the first part of this cycle, 150-Watt Photovoltaic cells harness the sun and generate energy that triggers the process of electrolysis, which means “to separate,” contrary to the folly’s binding goal. By running energy through two poles—an anode and a cathode—the reaction splits water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen.

03 Hydrogen, lighter than air, is used as energy storage and inflates the balloons at a rate of 2 grams per hour, causing them to float. Balloons filled with hydrogen are capable of lifting a lightweight textile tent, and in doing so “deploy” the architecture. At the established rate, it would take around ninety days to inflate the balloons completely. This cycle is completed once every season, only four times a year.

04 The tension between lift and weight allows different degrees of privacy and intimacy for the lovers, and sun, water, and fertilizer for the plants.

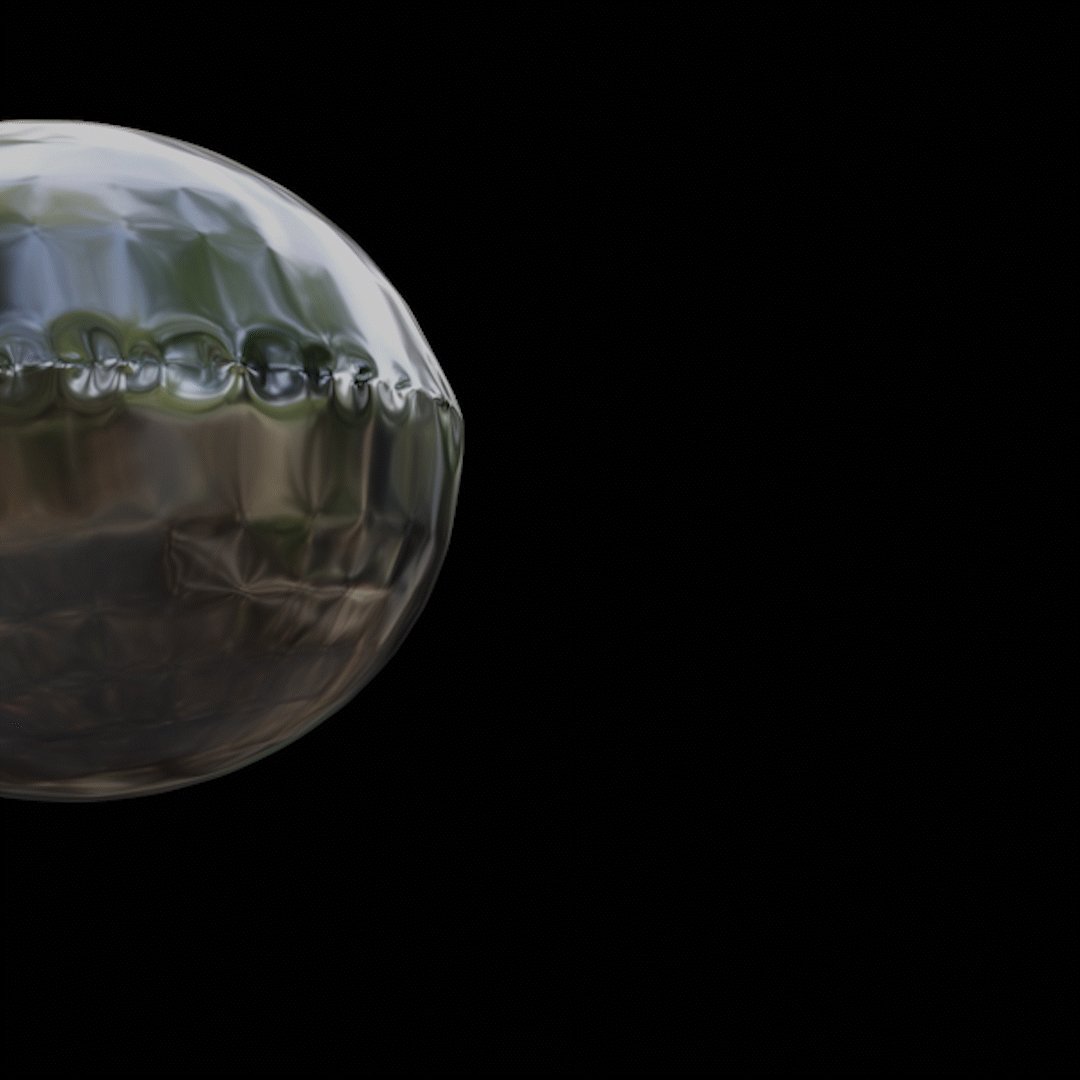

05, 06, 07 The mylar balloon at different stages of inflation and deflation.

There’s more in Issue 31.

Pablo Castillo Luna is an architect and MArch II candidate at Harvard GSD, where he explores the intersection of environments, time, and architecture. He is a co-founder of à la sauvette, an architecture practice dedicated to design, research, and cultural production. His work with à la sauvette on the spatial politics of urban public celebrations has been exhibited at the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Radialsystem Berlin, and the Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO) Ljubliana. Other projects with his practice include the curation and design of the exhibition Dancing the City (Bailar La Ciudad) and a publication with the same name. In the past, his architectural work has been awarded in the Spanish Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism, Concéntrico Festival, and exhibited at the Center for Architecture New York. Over the last years, has held fellowship positions for the Real Colegio Complutense at Harvard, Fundacion Arquia, and Future Architecture Platform. Prior to his graduate studies at Harvard, he was awarded a Diploma and a Master's in Architecture from the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, Spain) where he lived and practiced architecture and photography. Concurrently with his studies, Pablo held a researcher position at the metaLab at Harvard, and is now Teaching Assistant at Harvard GSD.